The Prime-Location Housing (PLH) Model sensationalised Singapore’s housing market earlier this year with its considerable changes to occupancy and eligibility criteria in prime districts. While the specifics of the PLH model are widely available, the more important question that few have answered so far remains: how will this affect my real estate journey?

The new measures introduced have far-reaching effects on those who invest in real estate, whether as an asset, home, or both, especially for those interested in living in the prime districts of Singapore. In this article, we will look at how each measure ripples through the market and affects aspiring buyers and sellers.

The notable restrictions under the PLH Model

Overall, we agree that the PLH model as a housing policy will be highly effective in its objective of making PLH units more accessible to the public. Notably, the PLH ruling will be effective in keeping these units mainly for homestay and will present themselves as desirable to families buying into the prime region for their own stay. Significantly, due to the resale levy as well as income cap (at 14k), it will be efficient in keeping the target audience as families interested in buying a home to stay for the long term, rather than investors looking to get a piece of the prime real estate. However, there will likely be many ripple effects that can only be visible many years down the road.

The PLH model introduces these four main changes from current mainstream HDB rules:

-

Minimum Occupancy Period: MOP is increased to 10 years from the original five years.

-

Renting: PLH homeowners may not rent out the entire flat (even after the MOP period).

-

Levies: Subsidy Recovery (SR) is implemented in addition to the existing resale levies.

-

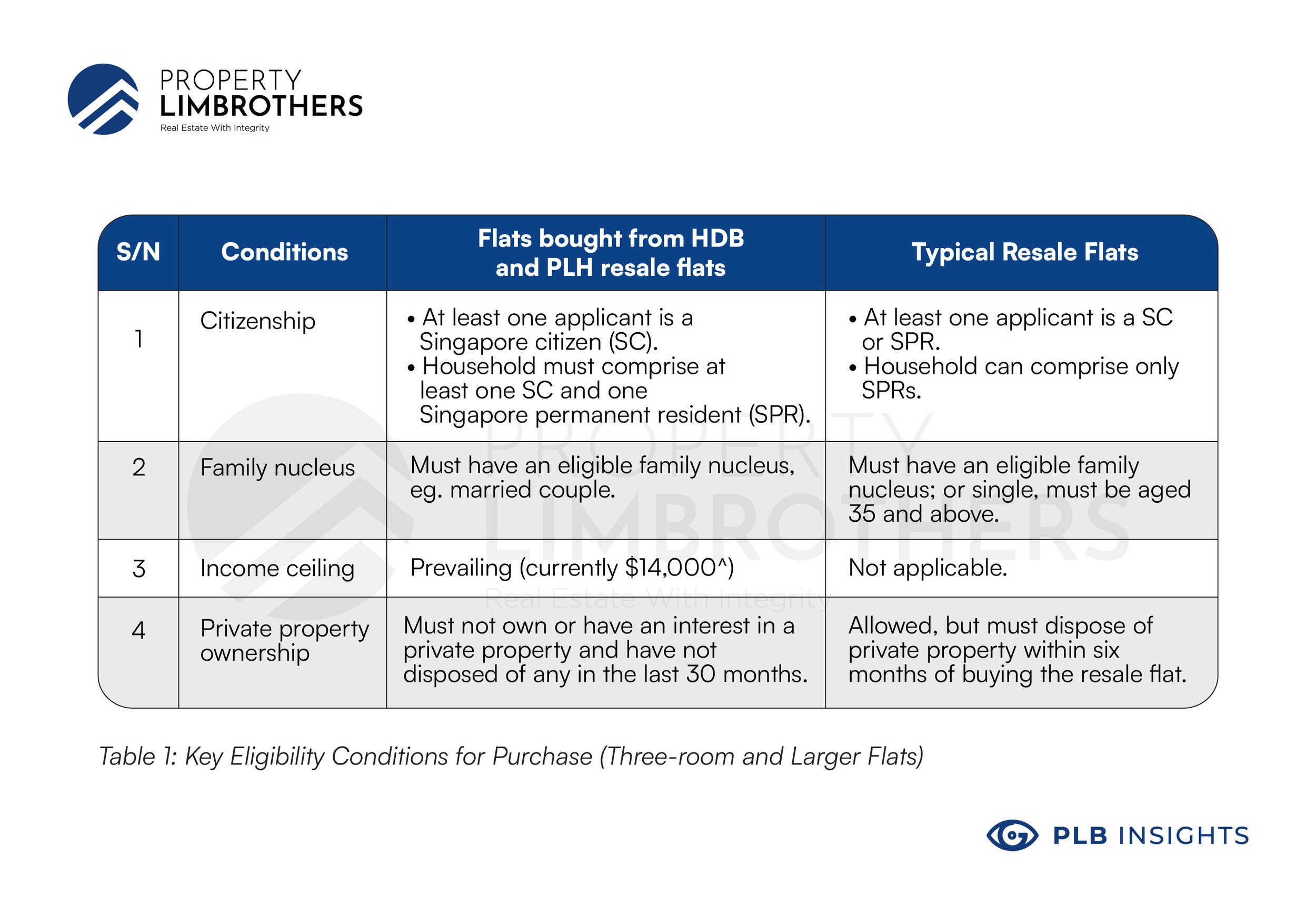

Eligibility: Requirements for these units are more restrictive in terms of citizenship and income levels.

Notably, many of these restrictions extend also to future buyers, which may limit the pool of buyers who can take over the property in 10-15 years.

Ripple #1: Increased demand for BTOs and resale not under PLH model

We expect that aspiring homeowners who plan to upgrade to their next property in the mid-term (5-10 years) are unlikely to buy PLH units. The increased MOP forces buyers to wait longer before they can eventually sell and upgrade. For most, the combined BTO build time and MOP duration will likely add up to 13 – 15 years, which is a long time to be staying in a first property.

For example, a couple of 30 year-olds would be looking at a 4-5 year construction time on their newly secured PLH BTO unit. After another ten years of MOP, they would be at least 45 years old when the flat is sold.

With such a long runway before the flat can be put on the market again, buyers face additional risks without having the option to sell earlier and having to miss out on good years in the market. This places significant restrictions on one’s real estate journey, especially for people who would have otherwise considered upgrading to further their real estate journey. Furthermore, it is also difficult to predict what the value of these units will be 15 years from now, adding more uncertainty for first-time buyers.

Because of this phenomenon, those looking to accelerate their real estate journey or simply to keep their options open will look elsewhere for their BTO units. For those buying resale flats, they may buy resale units outside of the PLH districts, or even within the PLH districts but excluded from the PLH model (such as Pinnacle@Duxton amongst others). This will drive up demand and prices for BTOs outside of PLH areas. Hence, HDB flats on the periphery of PLH flats that enjoy the same prime location without restrictions will likely see an increase in selling prices.

If you are an aspiring homeowner, you can definitely expect to see more competition for BTOs in the surrounding region.

Ripple #2: Fewer profits from the sale of PLH units

The implementation of subsidy clawback will lower the amount of proceeds made from the sale of a PLH unit.

Announced under the PLH scheme, flats sold to the open market by the first owners are liable to a subsidy clawback tagged to the resale price or valuation price at the time of sale, whichever is higher. While the specific numbers for clawback are not known publicly, buyers will be informed of the amount when they are applying for the unit. This number varies from project to project and will likely come in the form of a cash clawback similar to resale levies.

Shared recently, the first fleet of Rochor BTO flats will be liable to 6 per cent of the resale price or valuation, should they resell their flat. The rationale for such a subsidy clawback is that PLH flats require additional subsidies, factored into the BTO sale prices, on top of regular BTO flats, in order to keep housing in prime locations affordable.

Traditionally, BTO flats have been seen as attractive by many buyers who are looking to make some money out of reselling their property after the MOP period. However, deterred by the subsidy clawback, buyers who are expecting to buy into the prime location to make a windfall will now likely avoid flats under this scheme. This makes PLH units less attractive for buying and selling and more suitable as long-term family homes in the city. This leads us to our subsequent ripple effect:

Ripple #3: Audience for resale PLH will be restricted, and these restrictions will also be reflected in limited future buyers.

Due to strict requirements on citizenship, income ceiling, private property ownership, and marital status, the profile of buyers looking to buy these flats in the resale market will be much more restricted than typical resale flats.

This has several implications on the buyer audience.

First, buyers of flats under the PLH model can expect a general reduction of buyer audience for resale PLH units. Owing to the restriction that all resale buyers in the future must not have more than $14,000 in combined income, the buyer profile for these units can be expected to be limited in numbers. For flats not under the scheme, such regulation with regard to the income ceiling would only apply to those taking a HDB loan. With the PLH model, all purchases must now meet the income requirement, regardless of how they intend to finance their purchase. This requirement alone puts many buyers out of eligibility for purchasing these units.

Second, these PLH flats will be seen as significantly less attractive in terms of it being an investment for future rental yield. Prime location flats have some of the highest rental profits in Singapore, sometimes even higher than landed properties, due to the lower quantum at which the buyer purchases them. This makes them very attractive for investors to keep them as rental property after buying a second home. This was a viable strategy as the high rent is used to pay off any ABSD incurred from having a second property and also the mortgage. Now that PLH units can never be fully rented out as a whole unit, rental income is no longer as attractive and there is little incentive for investors to buy into the PLH units.

Third, there will be a reduced audience of buyers with high financial power. Since buyers must not have owned a private property in the past 30 months, private property owners looking to downsize to a HDB unit are forced to sell off their private homes first, rent for 30 months, and then purchase the PLH resale unit. This is a vast contrast from the rule for typical resale HDB units where buyers have to sell off their private property only six months after the purchase. The added hassle of renting and the uncertainty of selling their only property without another one secured is a big disadvantage for resale buyers downsizing from private property.

In our opinion, we reckon the rule was likely implemented because the government had significant data showing that many buyers of prime location HDB units are in fact, downsizing from their private property. These are possibly the same people who have the financial power to purchase $1M+ HDB properties. In order to combat high purchasing power pushing up the prices of these prime location HDBs, such a cooling measure was hence introduced. Because of this ruling, non-PLH units that still lie in the central regions of Singapore in contrast will likely be more popular and will grow even more rapidly.

Lastly, there will be a further reduction of buyer audience as PR/ single status buyers are excluded. Pure PR families who can afford prime location properties are now unable to purchase PLH units and will turn to other private properties or non-PLH units in the prime location. Similarly, singles above 35 are not eligible to buy resale PLH units. For non-PLH flats, these two groups of people would otherwise be able to purchase the unit without restriction. We also expect these two groups to have strong financial power, which again will be directed to other properties that do not have such regulations. Although the PLH model can be said to be extremely effective for keeping prime location flats accessible and affordable to the majority of Singaporean families, these many restrictions on buyer profiles again points to a reduction in buyer audiences due to stricter eligibility criteria.

However, the large reduction of buyer audience is not the only ripple effect that will arise from these novel and strict regulations. Coupled with a lowered buyer volume is the risk of a price ceiling on these PLH units.

Ripple #4: Price of PLH units will be capped.

The income ceiling requirement is a major limiting factor and it is likely to cause a price cap of $1.1M for PLH units.

Using a calculation for a couple with $14,000 combined income (the highest possible to be eligible), a Mortgage Servicing Ratio (MSR) of 30% allows for a maximum of $838,000 in HDB loans. At a 75% LTV, the max value of the property will be valued at $1.1M. By this fact, any price above $1.1M means that the couple buying the PLH unit will have to pay cash-over-valuation which acts as a strong deterrent for many. By contrast, the same couple being financed privately will use a TDSR of 60%, allowing them to take out a $1.87M loan.

This dampens the price appreciation on what future buyers will be willing to pay as the amount of loan they can borrow is limited by the MSR.

Conclusion

Predicting the future is all but an impossible task; however, we already have some clues of how the real estate market in terms of public flats in the prime locations will play out in response to the PLH Model. We expect that existing prime locations flats that are not governed by these cooling measures will see high demand and price appreciation. Longer-term effects will only be seen 15 years from now when the BTOs are built, and the MOPs have run out.

In the short term, we will see new families focus on BTO flats and explore options, including non-PLH properties in the same area. Meanwhile, the various restrictions will incentivise buyers to go for private property in prime locations if they can afford to do so.

For those who are familiar with the real estate market, you will realise that this is yet another cooling measure and a major one attempting to keep the real estate market in Singapore an affordable and inclusive one for all.

However, buyers who are huge fans of the central regions in Singapore and have no intention of upgrading into a private property within the next 10-15 years will definitely be the target profile that buys into these developments. These families will be happy to enjoy the subsidy provided for these flats and will definitely appreciate the ability to live in public housing at such prime locations.

In conclusion, every property is suited for a specific buyer profile, and being clear of your real estate needs will be helpful in terms of deciding whether this should be a wise choice for you. As usual, if you need any additional information or advice in your real estate journey, we are always happy to show you the place.