Singapore has been and remains to be a stable and reliable real estate market in the Asia-Pacific region. With its roots in prudent government planning coupled with the fertile economic ground, the Singaporean real estate market has experienced dynamic growth since its independence in the 1960s.

Before the 60s

Did you know that before the Housing and Development Board (HDB) and the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), there was the SIT? No, not the university – the Singapore Improvement Trust. Taking inspiration from similar agencies in India, the SIT which was established in 1927 was initially responsible for both housing and urban development before Singapore’s independence in the 1960s.

Public Housing

Image courtesy Roots.gov.sg

Before there were towering HDB flats, there were the SIT housing blocks. One look at your average SIT flats, and you would notice a nice blend of Western Art Decor and local shophouse features such as five-foot ways and spiralled staircases.

Dakota Crescent and more notably, the houses along Tiong Bahru and Seng Poh road are some of the examples of SIT housing blocks. In fact, 20 blocks of SIT flats in the Tiong Bahru Estate were granted conservation status by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA).

Yet these blocks were only 3-4 levels high, and units were much more spacious than the HDB flats we have now. Although the SIT housing blocks were the foundational building blocks for Singaporean public housing, they lacked the function to house enough residents to address a looming problem of overpopulation – a pressing issue in Singapore back then due to the postwar baby boom.

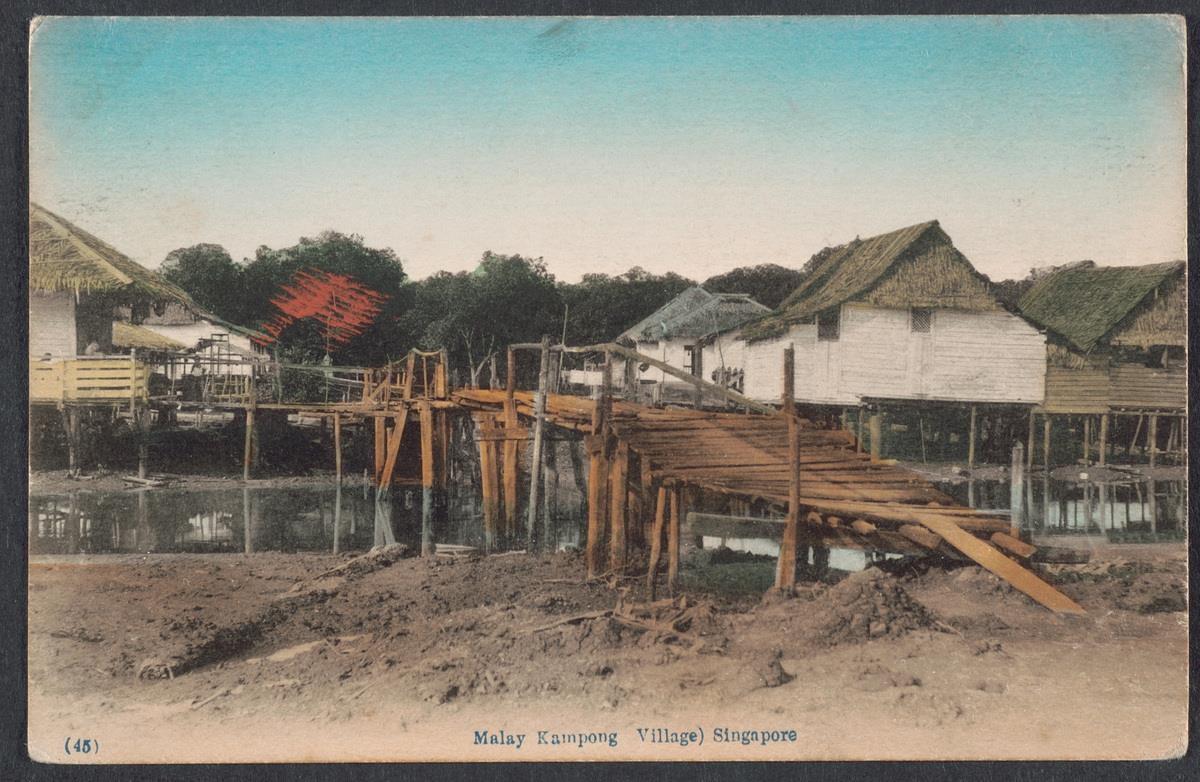

Furthermore, efforts by the SIT to build these flats were somewhat limited as whole kampung villages – clusters of homes made out of cheaper wooden material – needed to be razed in order to build these flats, which proved very unpopular amongst residents. The new flats also had relatively high rental costs, further discouraging residents from moving into these SIT blocks.

So who owned private properties back then?

Private property was often owned by the more affluent English and local businessmen who had made their profits during the colonial period. Yet interestingly, a portion of the middle class – essentially, not-so-rich members of the colonial service – owned what we know as co-operative housing (mainly through loan schemes).

Usually built by societies or unions, the most prominent housing society was the Singapore Government Officers Co-operative Housing Society Limited (SGOCHS, established in 1948). With projects from Thomson Road to Paya Lebar, it peaked in the 1960s, having established over 100 co-operative estates.

Independence Years (the 1960s and 1970s)

Public housing entered the spotlight after the PAP took power in 1959. With overpopulation already reaching unsustainable levels, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) was established to replace the SIT to better address this issue. The HDB, and later on, the larger-scale URA, would work in tandem to, quite literally, change the face of the Singaporean landscape.

Changing neighbourhoods

Image courtesy Roots.gov.sg

Before the 1960s, for many Singaporeans, kampung villages were the norm. Incomes were relatively low back then, so wooden squatters were often set up along urban areas to better cater to their livelihoods. However, these kampungs were unsanitary – the villages lacked basic amenities, and as homes were cramped together, kampung villages were a haven for disease transmissions. These homes were also made of attap leaves, which are a great fire hazard.

Image courtesy Roots.gov.sg

Remember Murphy’s law: anything that can go wrong will go wrong. The Bukit Ho Swee Fire proved just that; a major fire in what now is the Tiong Bahru housing estate left as many as 2,833 families homeless.

Yet every tragic event has a silver lining. Cheap, low-cost flats were swiftly built by HDB around the Bukit Ho Swee area, allowing homeless residents affected by the fire to move into these new residences.

The HDB flats, unlike the SIT block, were hence much more widely received due to the HDB’s newly-gained credibility. In addition, HDB flats were cheaper and could be bought by one’s Central Provident Fund (CPF).

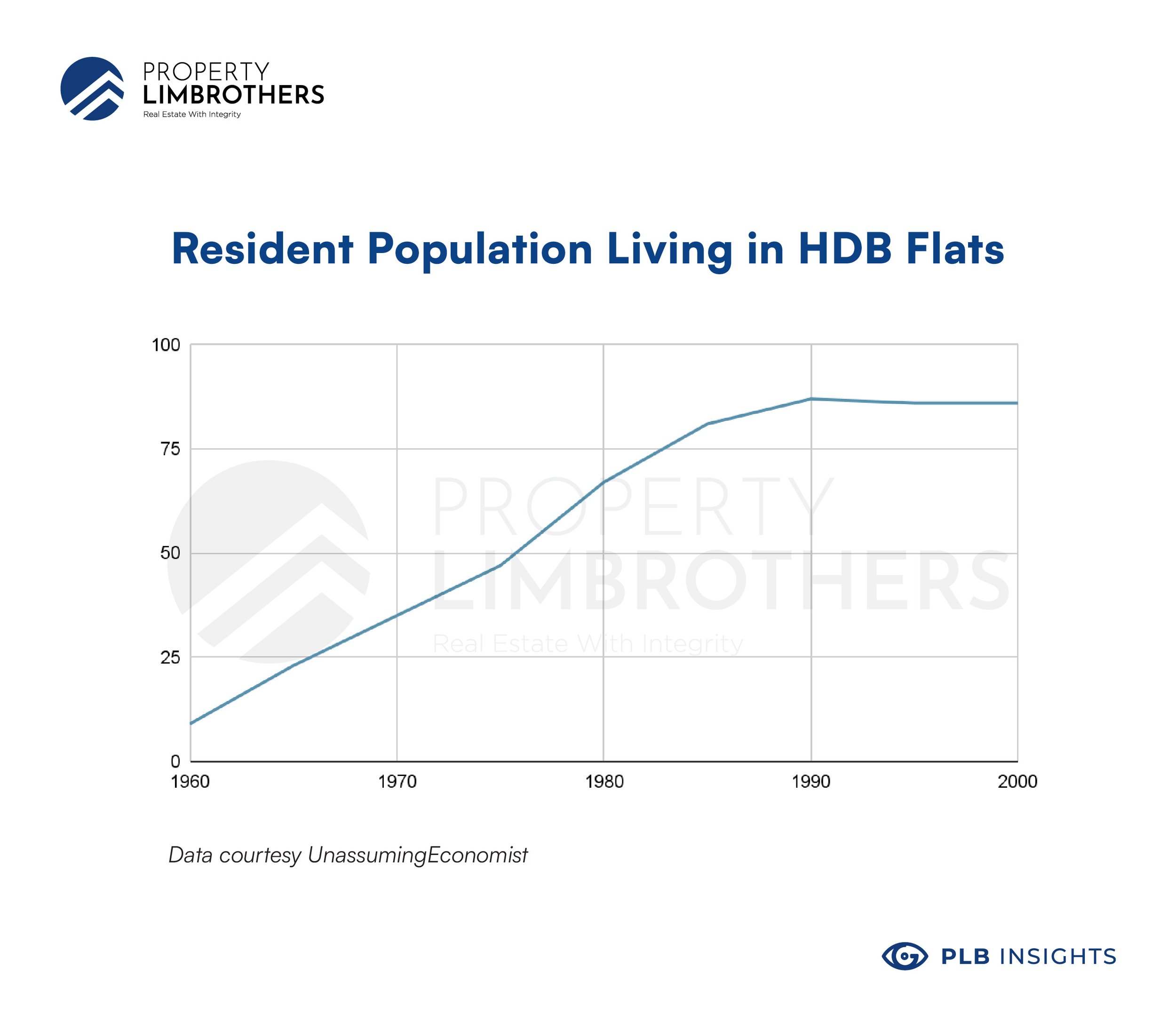

As such, by 1970, a third of Singapore’s population had been living in public housing (35% to be exact), a massive jump from 9% in 1960.

The HDB resale market was also established in 1971, allowing HDB flat owners to sell their units after serving a minimum occupancy period.

Other public housing efforts

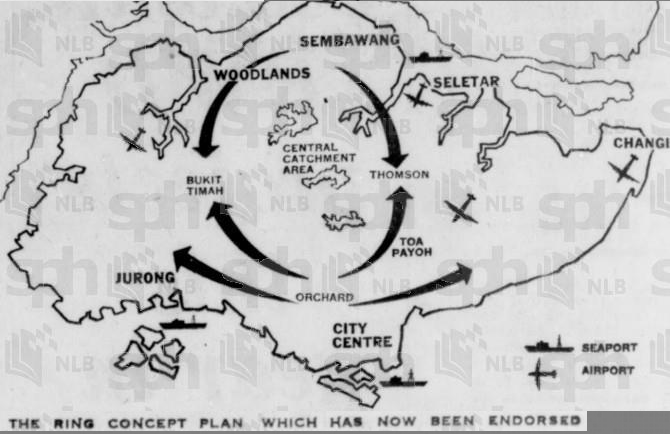

On top of HDB efforts, in 1971, a ‘Ring Plan’ proposal for the city-state was put into place. The government would also facilitate the building of high-density development areas around the Central Area as well as on the southern regions spanning from Jurong to Changi.

These efforts were part and parcel of grand infrastructural plans to let Singapore have the capability to house 4 million residents by the end of 1992.

Image courtesy Eresources NLB

Industrialising Singapore in its independence years

Singapore, while a nascent nation, had ambitious economic goals. The goal was to thrive despite being a vulnerable nation-state with little to no resources and to become a global city. And these goals were reflected well in its land planning.

As mentioned earlier, to facilitate rapid industrial development, land in the Jurong area, and later in Sembawang and Seletar were set aside to allow foreign businesses to set up factories in Singapore, bringing in thousands of lower-wage jobs.

In order to fully facilitate the development of the Central Area – think not just Orchard Road, City Hall, but also Toa Payoh and Ang Mo Kio – the URA was established in 1974. In the latter half of the 1970s, it began running campaigns to optimise land use by upgrading existing infrastructure and clearing slums to make way for offices and malls.

By the 1980s, not only did the URA allow for the building of factories along what were once muddy expanses, but it also gave rise to the retail, tourism and finance industry in Singapore.

Budding Prosperity (the 1980s)

Image courtesy Roots.gov.sg

As the government began transitioning the Singapore economy to develop its comparative advantage on more capital-intensive industries such as education, information technology and healthcare in the 1980s, average incomes rose in kind. The Singaporean economy was well on its way to development.

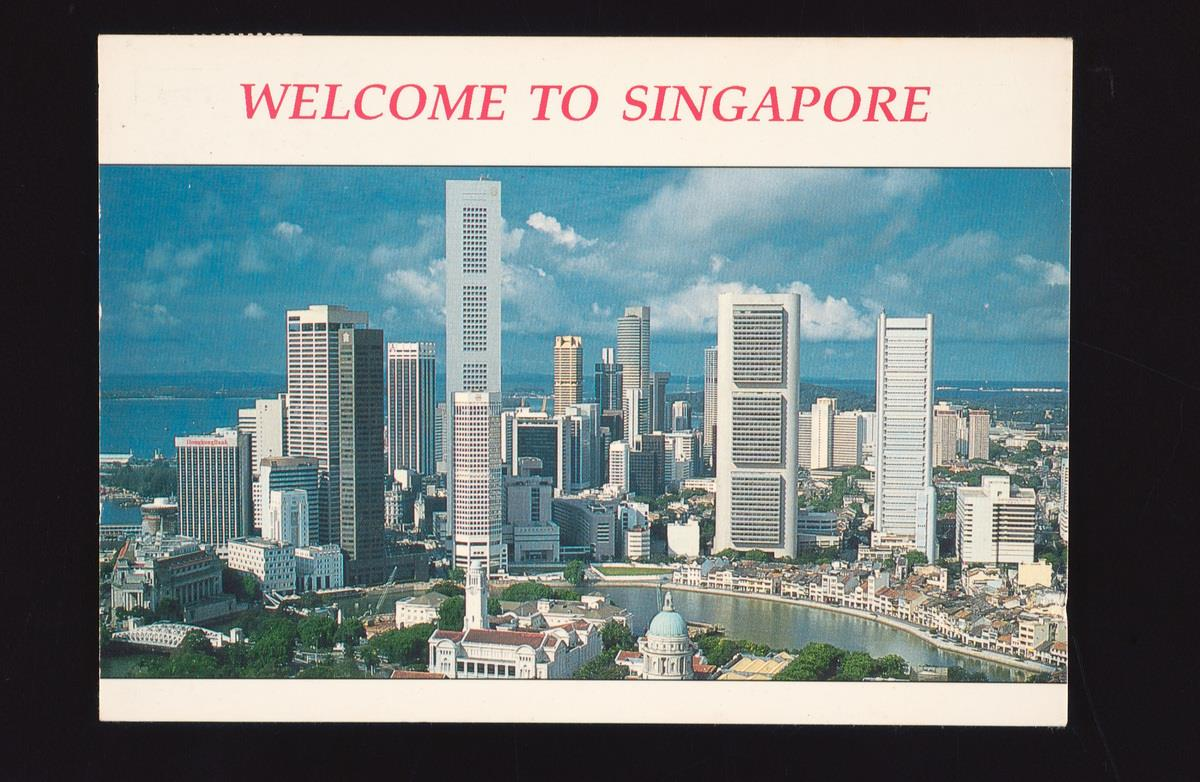

By 1985, four-fifths of its residents now lived in public housing. The Central Area never looked like it once did in the 1960s; once reclaimed land now stands the Central Business District (CBD). Slums were replaced with commercial centres and flats. Orchard Road was also revamped, and now more closely resembles the tourist haven it continues to be today.

Higher Incomes Transformed Housing

Image courtesy Roots.gov.sg

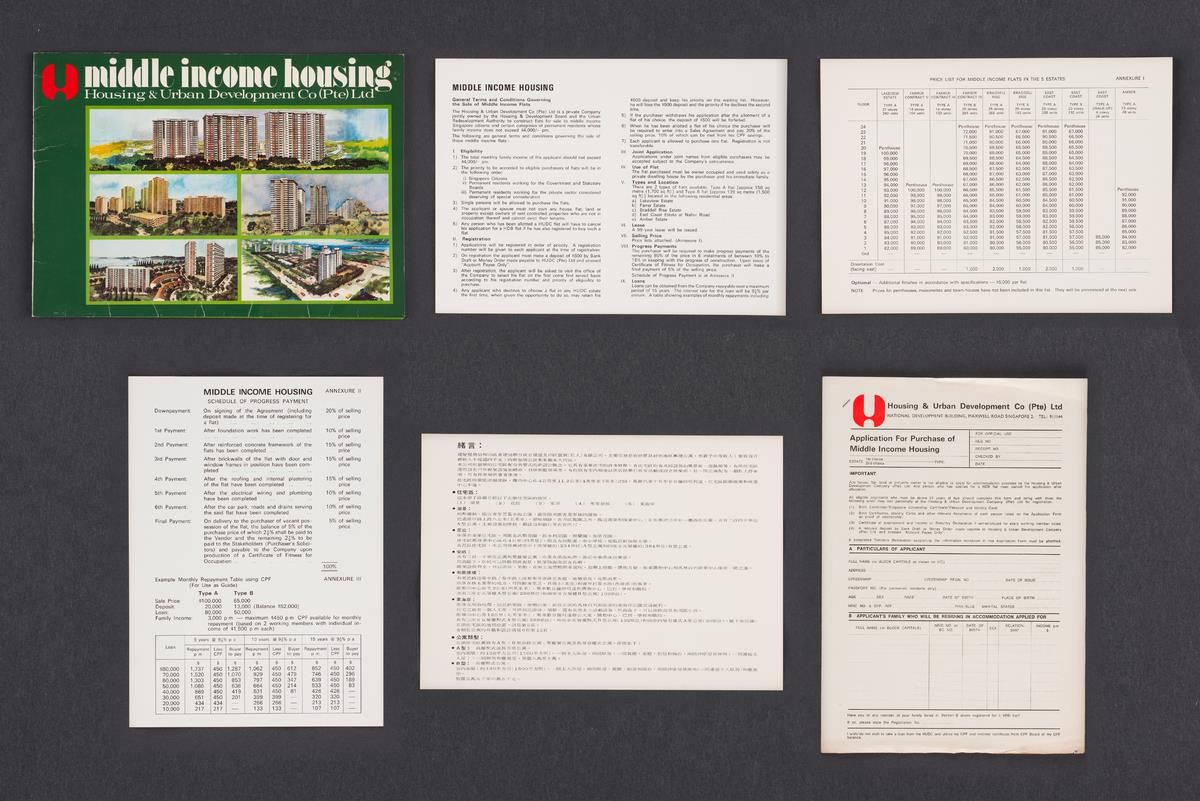

Aside from the HDB, other organisations such as the Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) and the Housing and Urban Development Company (HUDC) made their flats in the 1970s.

The former aided the government in providing housing for residents in Jurong and Sembawang. At the same time, the latter helped provide alternative public housing for middle-classed residents who were not able to afford condominiums.

In the 1980s, there were also changes to specific regulations surrounding public housing.

Image courtesy Roots.gov.sg

The first one was pertaining to singles owning property; before the 1980s, singles were allowed to buy HUDC flats, and for a brief stint in 1980, they were even allowed to make use of their CPF to do so.

However, in 1982, when HDB took over the management of HUDC flats, regulations changed; singles were restricted from obtaining HUDC flats but were nevertheless placed on a ‘waiting list’ until they started families.

Designs of HDB flats and variations of HDB units began to change as well. The HDB would introduce larger executive flats in the 1980s to cater to more well-to-do families.

A changing commercial landscape

Image courtesy Savills

Singapore was already a fast-growing economy; as planned by the URA, the Central Business District (CBD) became Singapore’s financial and business hub, home to its emerging white-collar industries.

By the second half of the 1980s, the CBD was home to record-breaking skyscrapers. The former OUB Centre (now One Raffles Place) was Singapore’s tallest building during its completion in 1986. Now it is just one among the four buildings built up to 280m (Singapore has a maximum height of 280m allowable for buildings). In fact, Guoco Tower, completed in 2016, gained special permission to be built at 290m in height, towering over the other skyscrapers in Singapore.

Developments in the 1990s

By the 1990s, Singapore had already earned its status as a developed country. Having first-world status meant that its residents had first-world incomes. As such, with it came many innovations in the real estate sector.

Public Housing Needed a Makeover

Public housing took another revamp during the 1990s, as various schemes were implemented to facilitate infrastructural upgrades, especially with HDB blocks. Most notable was the Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme, where older blocks were – instead of simply upgrading the flats themselves – demolished to better make use of the land for redevelopment.

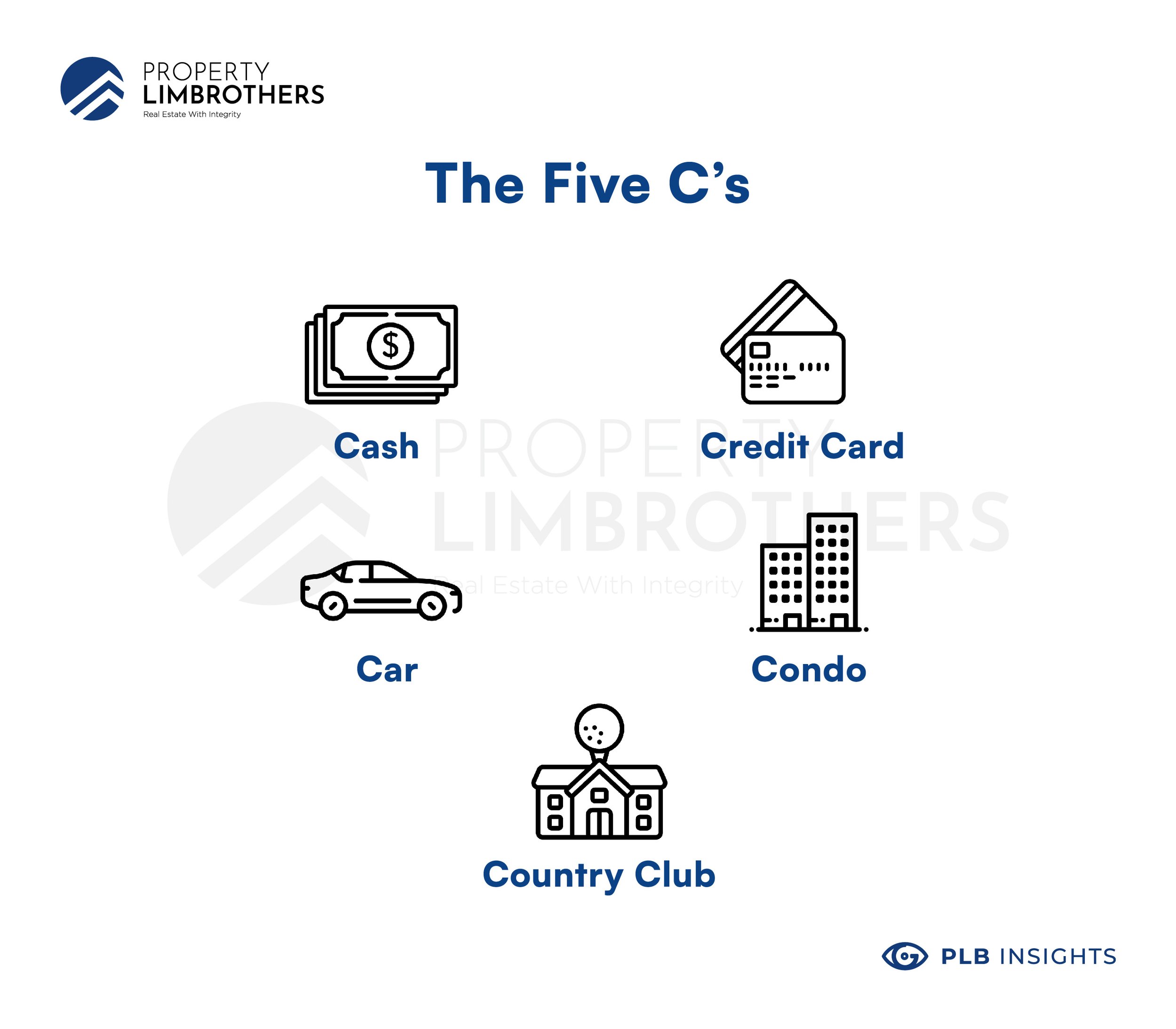

A more prominent middle-class Singapore meant that public housing had to keep up with the rising demand for private properties – remember the 5 Cs?

The ‘Five C’s’ in the Singaporean context are a play on the ‘Five C’s of Credit’, where, lightheartedly, the material aspirations of many Singaporeans may be condensed into five C’s:

As such, executive condominiums were introduced to the public housing market with similar traits to private ones. Newer HDB blocks had more diverse designs through Design and Build schemes, where the government would partner up with private architects to come up with layouts for these newer apartments.

Reforms and Roadmaps (2000s and 2010s)

As Singapore entered the 21st century, its real estate market faced newer challenges: the most novel being the risk of an overheating housing market, especially in the face of growing foreign participation and higher incomes among residents. Properties were also rising in demand as more residents were financially able to view real estate as a form of investment.

The early-2000s: Deregulation of the property market

The HDB housing market would be deregulated even further in 2005. The Design, Build and Sell (DBSS) scheme accorded private developers the freedom to draw up and construct and make a profit off of their own blocks. However, as the flats turned out to be too expensive and of less value for money – with persistent defects and lack of condo facilities – no new DBSS flats were made after 2011.

Growth of the private housing market

Greater foreign participation and higher incomes in the real estate market meant elevated demand for condominiums.

This boosted the property market to alarming levels: property prices rose about 36% between 2006 and 2008, driven mainly by rising demand for high-end properties.

The 2009 financial crisis (and what this meant for the housing market)

One defining moment of the new century for the real estate market would be the 2009 crisis. The Singaporean real estate market, having been deregulated, had been overheating. Stamp duties were reduced by 30%, and the loan-to-value (LTV) limit of 80% introduced in 1996 was raised to 90%.

Therefore, the second half of the 2000s and 2010s signalled an increasing trend of regulation: the Additional Buyers’ Stamp Duties (ABSD) – a term you know well in light of last year’s end-of-year cooling measures – were introduced in 2011 on top of existing stamp duties.

Three rounds of Cooling Measures – ABSD and LTV restrictions – were introduced in 2011, 2018 and 2021 to address subsequent overheating concerns in the housing market.

Demand for private property continues to rise.

The 2009 slump, with its accompanying slews of regulation, did not dampen too much confidence in the Singaporean real estate market.

Be it due to existing HDB flat regulations over single-person households or the enduring idea of the condominium unit as a status symbol, despite higher LTVs and ABSDs; more families are obtaining private properties.

From 2010 to 2020, more families now live in condominiums (from 11.5% to 16.0%), fewer live in HDB flats (82.4% to 78.7%), whilst landed property ownership stayed around the same percentage range (from 5.7% to 5.0%).

The Overview of Singapore’s Real Estate Development

Singapore has come a long way in terms of its Real Estate Development, from attap houses in kampung villages to the formation of Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) in 1927. Then the establishment of the Housing Development Board in 1960 to take over SIT in the public housing sector. After which we had the Urban Redevelopment Authority to oversee urban development in Singapore – putting out works such as the URA master plan which sets the foundation for all real estate development in Singapore now!

It is quite evident that the government has put emphasis and priority on Singapore’s Real Estate in terms of delegating intellectual prowess and monetary resources to develop our tiny little red dot. Both Singaporeans and Foreign Investors can be rest assured of our future development and the intrinsic value that our real estate will hold!

If you’re looking to invest in Singapore’s Real Estate whether you’re a Singaporean or a Foreign Investor do feel free to contact us! Click here to contact us now!

This article is written in conjunction with our #InvestorsSeries on Youtube. We drop nuggets of wisdom for you to learn more about Singapore’s property market! From frequently asked questions to market analysis, we’ll take you through them all with the PropertyLimBrothers team.

Interested in if We Are Headed for a Bullish or Bearish Real Estate Market in 2022? We delve into that in our insights article here!

To check out our Investors Series Season 1 click here!

And for Investors Series Season 2 click here!