Luxurious landed homes are punctuated throughout the world today. These mansions brimming with palatial fittings and architecture have various terms in different countries. For example, these are termed “Acreage” in Australia, “Lifestyle Properties” in New Zealand and “Mid-Century Modern Style Houses” in the United States. Well, different folks, different strokes.

In Singapore, these grand dwellings are termed Good Class Bungalows, or GCB for short.

When one mentions ‘landed property’ in Singapore, we tend to think of the terraces that lie in Loyang, or the detached houses in the Cluny Hill area. Good class bungalows (GCBs) are something not commonly seen in the picture, as it is often perceived as an unachievable fairytale. As a symbol of prestige especially in the real estate market, these bungalows have a whopping land size of at least 1,400 sq m scattered within 39 different prime areas in Singapore.

With the tons of planning constraints imposed by URA to adhere to and the limited land allocated for GCBs, these factors contribute to the prestigious and exclusive status of GCBs. But before we go in-depth, let’s understand how GCBs came about, and how it led to where GCBs are today in the real estate market.

How it all started

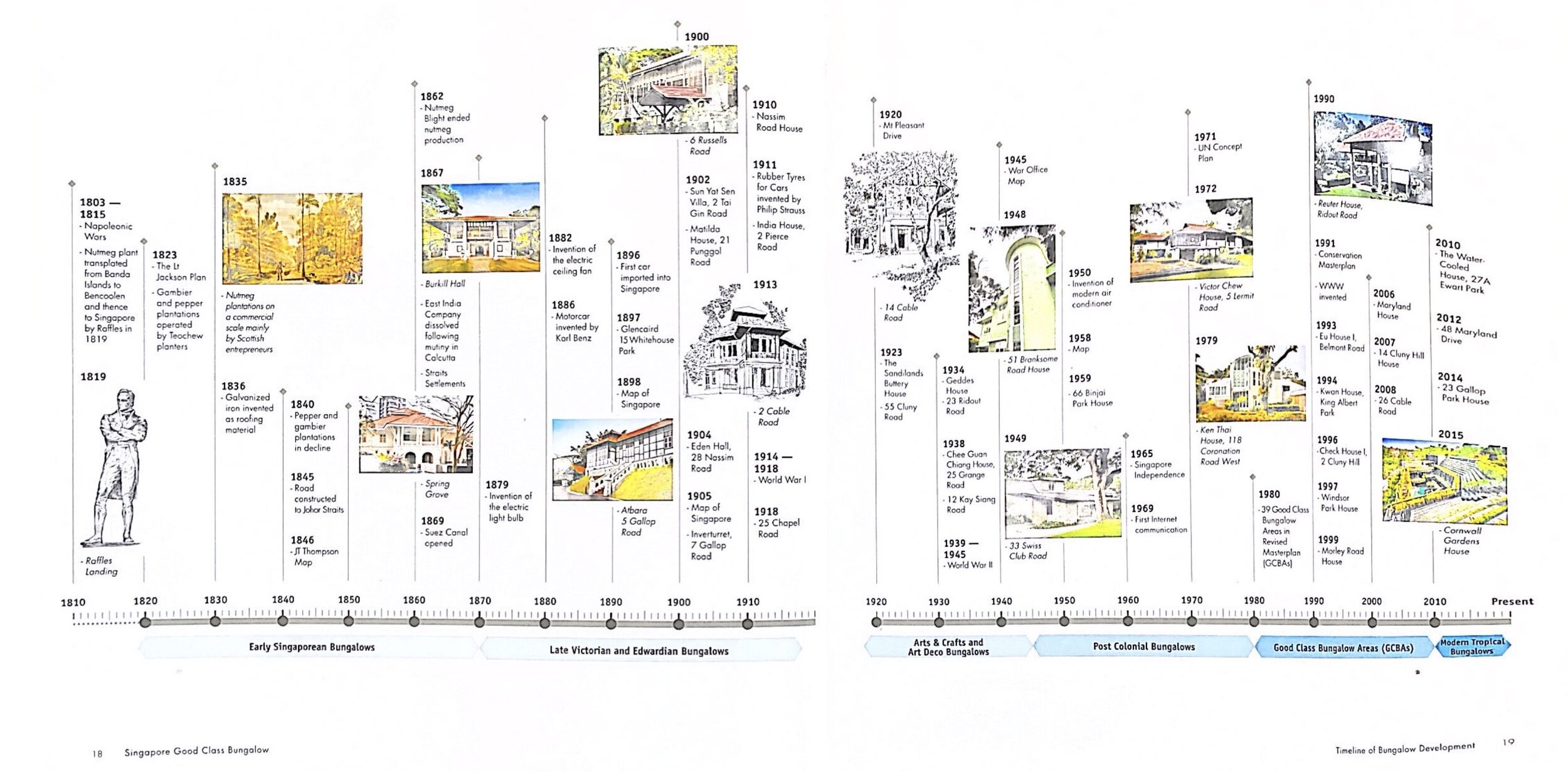

Early Singaporean Bungalows (1810s to 1870s)

GCBs were established in Singapore’s real estate market in 1980. But before that, they were classified together with the other types of bungalows in Singapore and surprisingly, the history leading to their establishment goes way back to the 1800s when Sir Stamford Raffles first arrived in Singapore.

The history of bungalows in general started out in the 1800s around the time when Sir Stamford Raffles first arrived in Singapore. The bungalows from the 1800s all the way till 1870s were commonly referred to as ‘the Early Singaporean Bungalows’, which are typically located near to plantations in the North and west of the original settlement.

Taking a look at the some of the artist impressions of these Early Singaporean Bungalows, it might be a bit unflattering if we were to compare it to the GCBs we are familiar with, but these bungalows are still part of the history that actually leads to the GCBs we see today. Looking in-depth into the design of the bungalow, it can be derived that the general design is influenced by indigenous Malay houses to adapt to different weather conditions.

Image courtesy Raffles Institution School Magazine

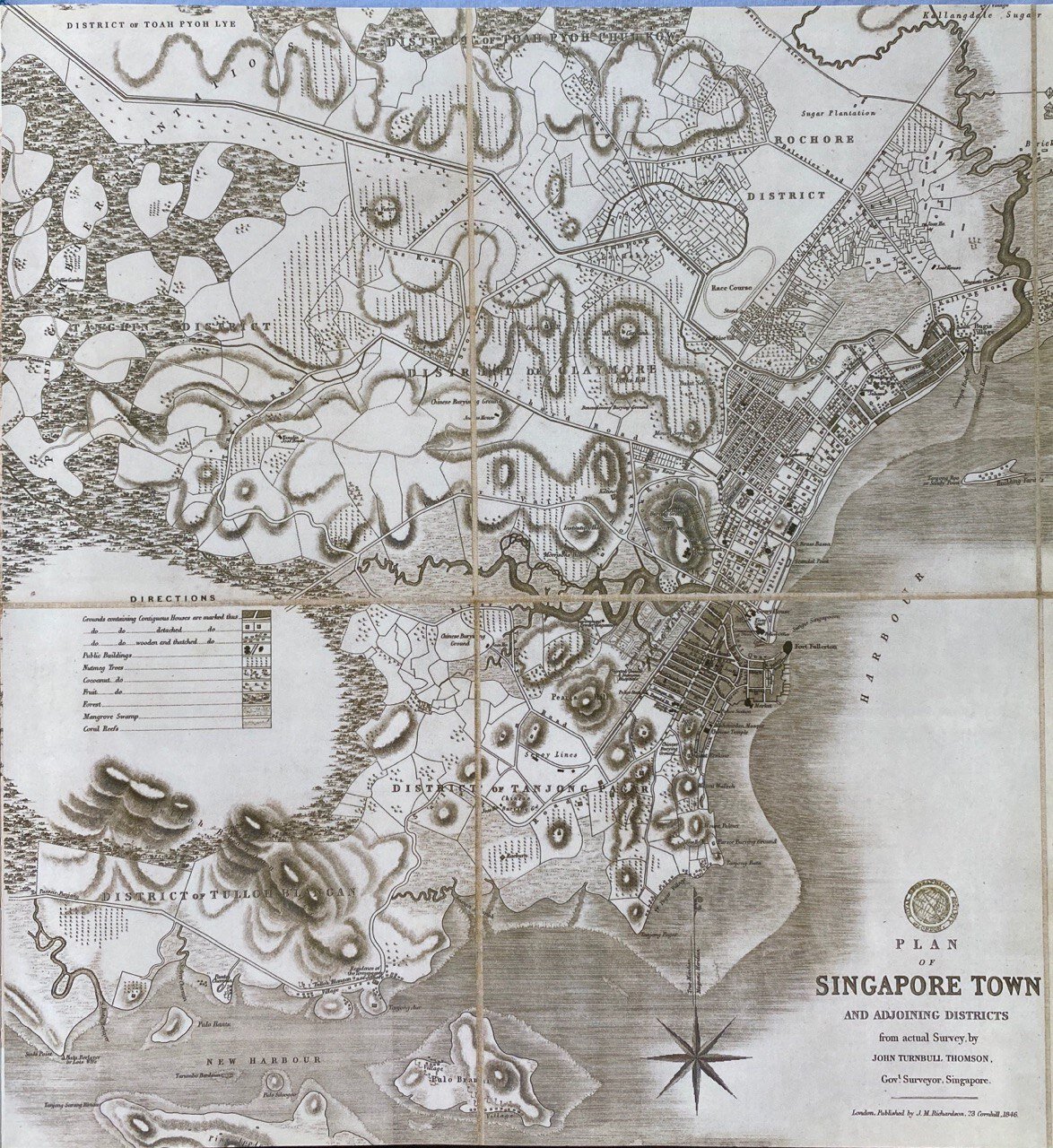

Taking a looking at the map from a survey done by John Turnbull Thomson in 1846, it can be observed that there are quite a few plantations and “Early Singaporean Bungalows”, or in other terms ‘contiguous houses’, that sprout out around plantations nearing to the coastal lines towards the south of Singapore.

The plots of freehold land that the bungalows sit on used to belong to the Chinese who were granted the land for plantations during the 1830s to 1840s. However, they started heading North to Johor in the 1850s due to the “slash and burn” agricultural practices leading to destroyed forests and decreased functionality of the land.

Taking over these were enthusiasts, consisting mainly of Europeans, to form the Singapore Agricultural and Horticultural Society for experiments with alternative crops. Also within the plots of land they own are their residential bungalows. Over time when the business for these crops started to go downhill in the 1860s, this group of enthusiasts started to dispose of or sell off parts of the land they own and keep the portion of the bungalows.

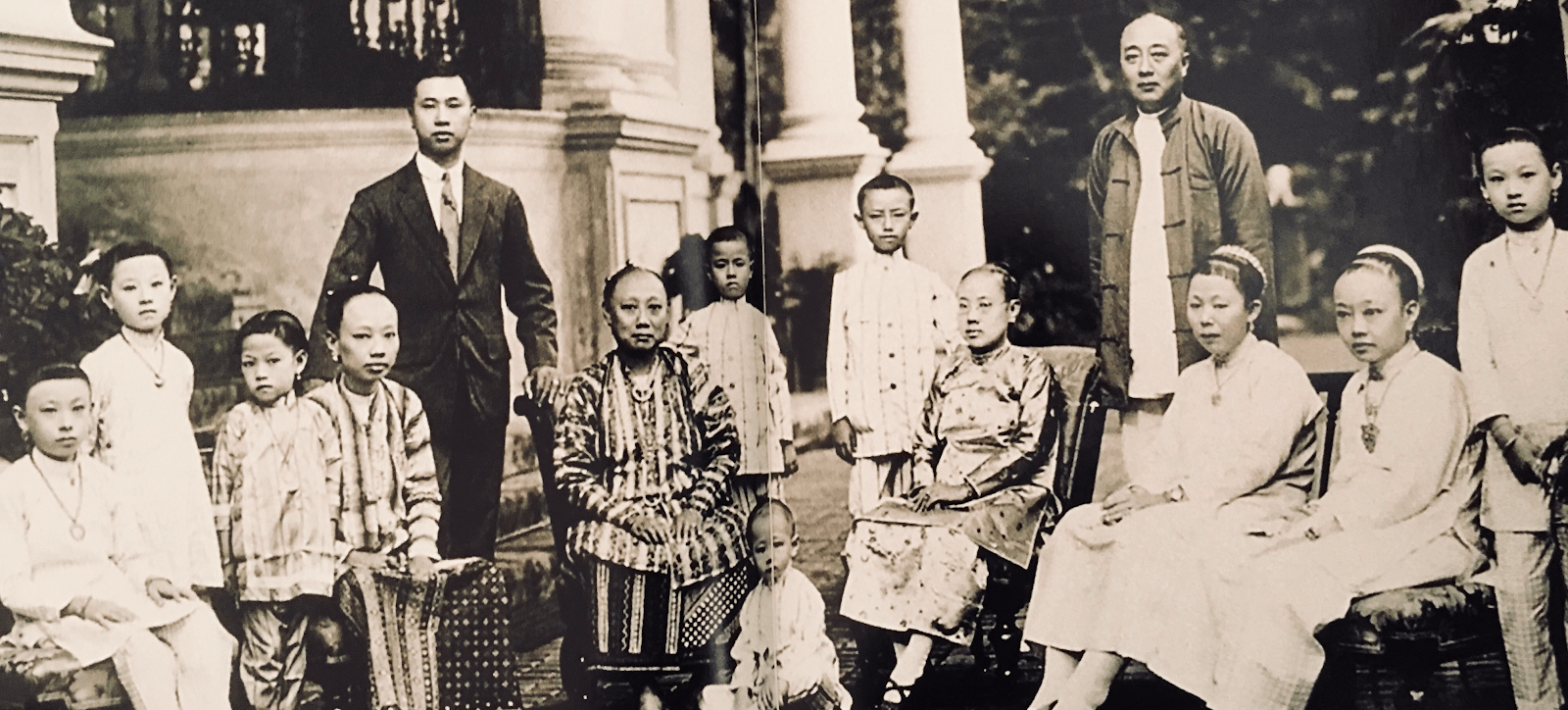

Image courtesy Chinachannel.org

It is also during this period of time that wealthy Chinese merchants came back into the picture. Because of their increasing affluence and extending family size as well as the political and economic issues faced in China, these merchants migrated to Singapore, bought up the plots of redundant plantations and transformed them into exclusive residential areas.

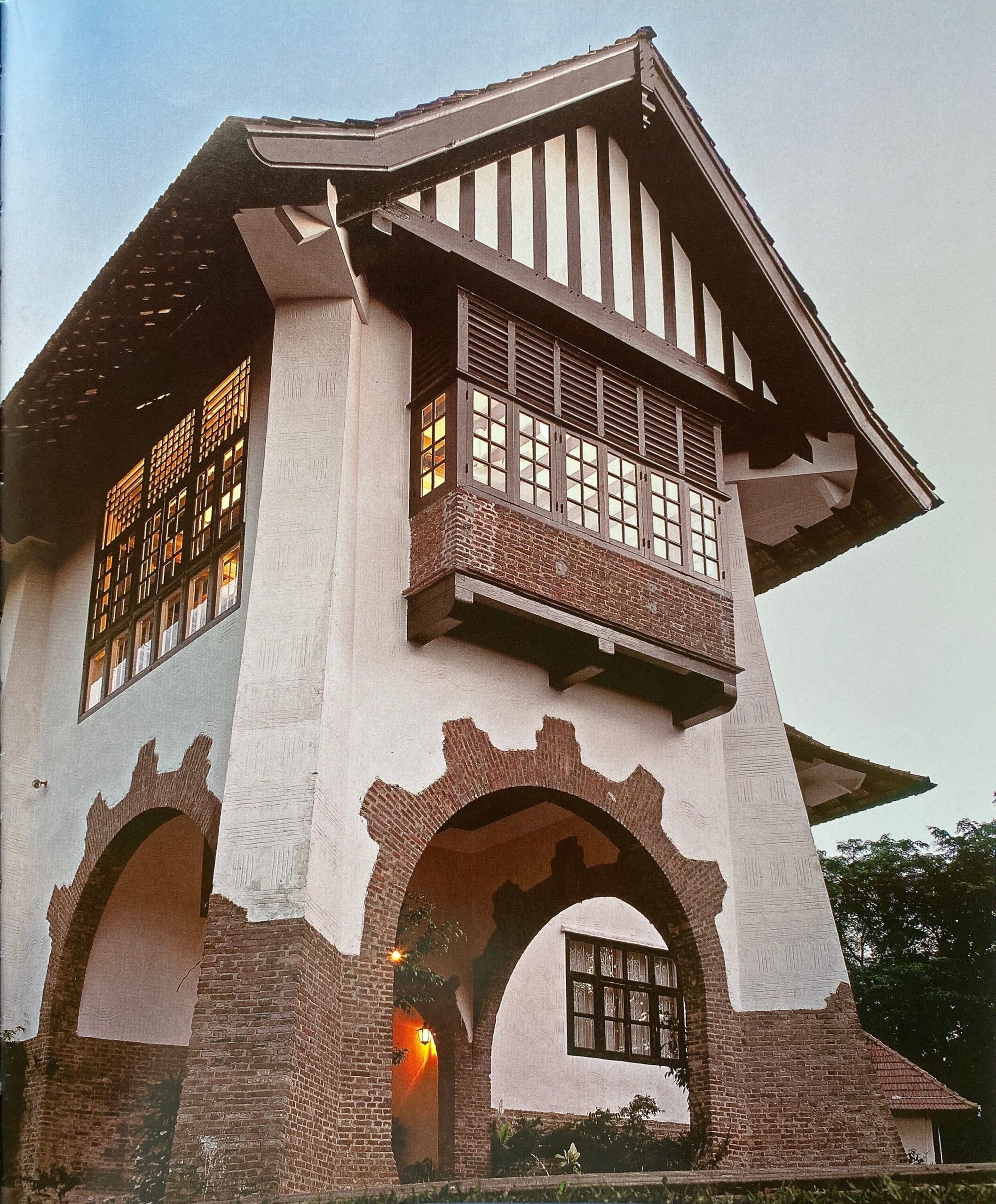

Sun Yat Sen Bungalow originally built for a Cantonese merchant in 1902

These factors led to the change in the style of the bungalows and their locations, going from the “Early Singaporean Bungalows” to the “Late-Victorian and Edwardian Bungalows”. Also, some areas allocated for GCBs today came from these plots of land, which we will talk more about later.

The Late-Victorian and Edwardian Bungalows (1870s to 1910s)

Going into a new time frame between the 1870s and the 1910s, this is where the styles of the bungalows started to shift towards what was described as the Late-Victorian Style. The Victorian eclectic influences in these bungalows are evident through its gothic and asymmetrical architecture designs, and is part of the Arts and Crafts movement espoused by John Ruskin, William Morris and Philip Webb.

An increasing number of property investment companies started coming into Singapore in the middle of the 19th century, which also led to more plots of land being sold to these wealthy businessmen or companies who seeked residences for their staff.

Gothic influences to architecture also came back into the picture in the 1860s when they were revived, and these bungalows are commonly referred to as “Mock Tudor”, or what we know as the Black and White houses. There are still some Black and white houses in Alexandra Park Estate nearing the south of Ayer Rajah Road.

Image courtesy Business Times

Although these bungalows have significant history behind and contributed to most of the landed homes we see around today, most of them remain as typical landed homes that are preserved and are mostly not part of the GCBs.

Arts and Crafts, Art Deco and Modern Movement Bungalows (1920s to 1940s)

You might be wondering then, if the Late-Victorian and Edwardian Bungalows are not part of GCBs today, why are they still mentioned in the history of GCBs then? To clear out the air, the Arts and Crafts Movement in that time frame got carried forward and stayed on in between wars, alongside the architects who picked up after the aftermath of the economic depression in the 1930s. This actually influenced a series of prestigious and exclusive bungalows to spring up around different areas in Singapore, which are part of the GCBs areas we see today.

In the 1920s after the first world war, an increasing number of European officials and companies as well as Chinese Merchants came to Singapore. With that, they seeked company homes for their staff, or residential homes for their personal use. And all these bungalows displayed hints of the trends in the Arts and Crafts movement which are also passed on to the next generations.

Nearing the 1930s, this is where the architecture of the bungalows built displayed the influence of Art Deco, which is an influential visual arts design style that first appeared in France. This was together with the Modern Movement that grew the population of bungalows in Singapore.

Post-Colonial Bungalows (1945s to 1980s)

After the Second World War in which Singapore was involved as well, Britain started to recognise Singapore as a state rather than a crown colony, and within the next two years Singapore was declared as a sovereign and independent nation.

Image courtesy NUS Libraries

During and after gaining independence, the former crown colonial geography shifted drastically and residential bungalows started to shift inwards as seen in the 1958 map prepared under the direction of the Surveyor General Malaya. Also during this period of time, more architects came into the picture having styles expressing strong, independent modern identity to divest themselves from the colonial past.

This move was also influenced by the plans from town planning experts in the United Nations. As requested by the Singapore government, the plans were meant to assist Singapore in tackling her development problems.

Meanwhile, belonging to these architects are splendid bungalows that reflect their architectural style. Rich in design and history, some of these areas became the GCB areas that we know of today. In fact, some of the bungalows still exist today.

The Emergence of Good Class Bungalows we know today

Now, you may think, after all this rambling about history and how a portion of them leads to the GCB areas and even the GCBs themselves today, when exactly were they established in the Singapore real estate market?

There were no exact records of when or how the term “Good Class Bungalow” came about. What is known, however, is that efforts were made to seriously classify landed properties in the 1970s. Also, with a thorough examination of the official documents during the planning and classifications, it was noticed that the term was invented in the early 1980s.

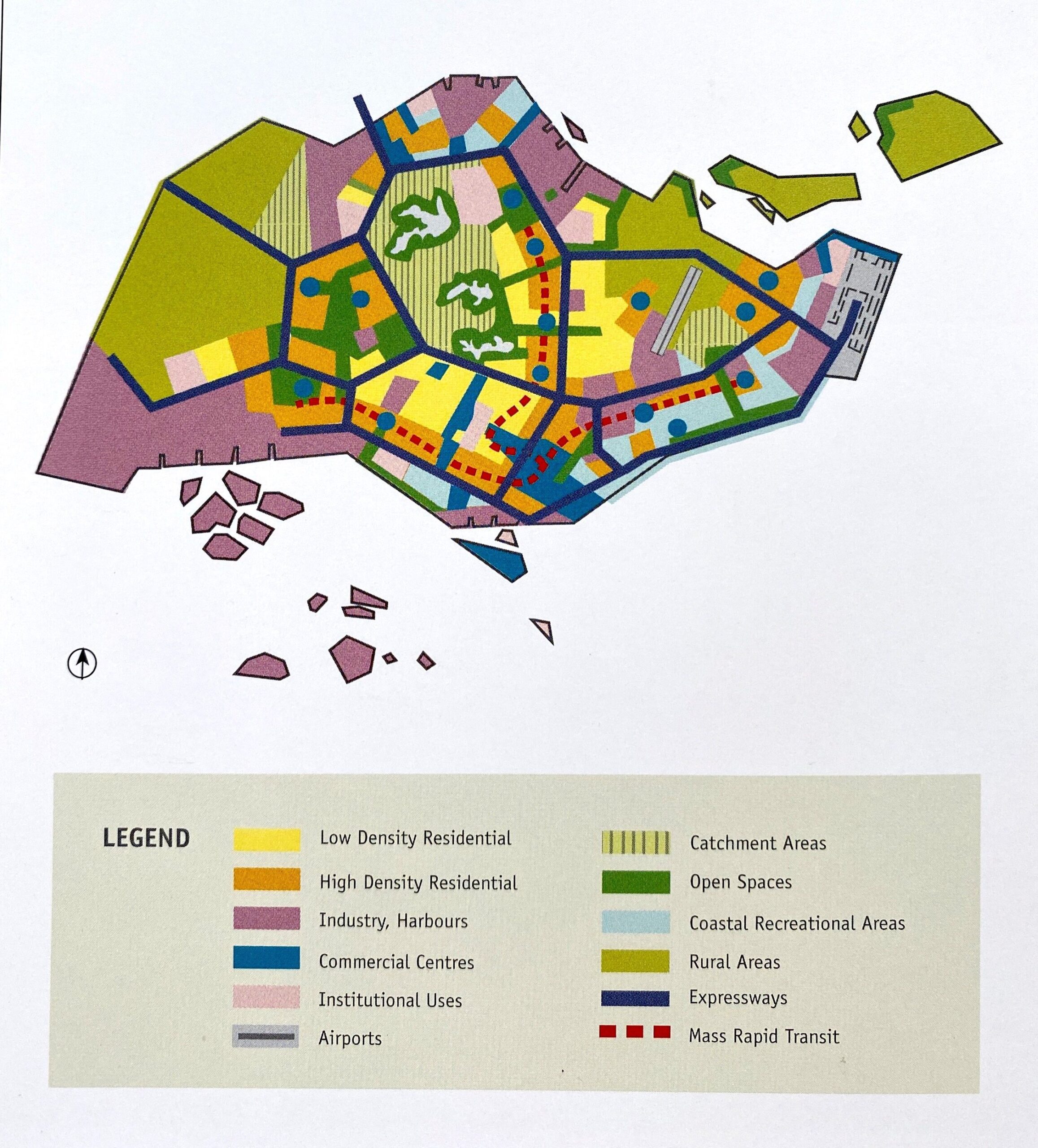

Image courtesy URA

The 39 different areas allocated specifically for GCBs were first identified in the 1980 Revised Master plan produced by the government’s Planning Department, with the intention to “preserve and enhance such development areas and their environmental character by allowing bungalow development only on compatible plot sizes within the areas concerned”.

Not surprisingly, if we were to take a look at the map which indicated the 39 different GCB areas and compare it against the 1971 concept plan, these GCB areas remain within the “low density residential” areas allocated.

Good Class Bungalows, defining prestige

A main factor that makes these GCBs so exclusive is precisely because of how it can only be built in these 39 assigned areas within the more popular districts 10, 11, 20, 21 and 23 in Singapore. Also with many restrictions by URA in place for a bungalow to be considered as a GCB, it is henceforth much pricier and much of a hassle to build and own a GCB.

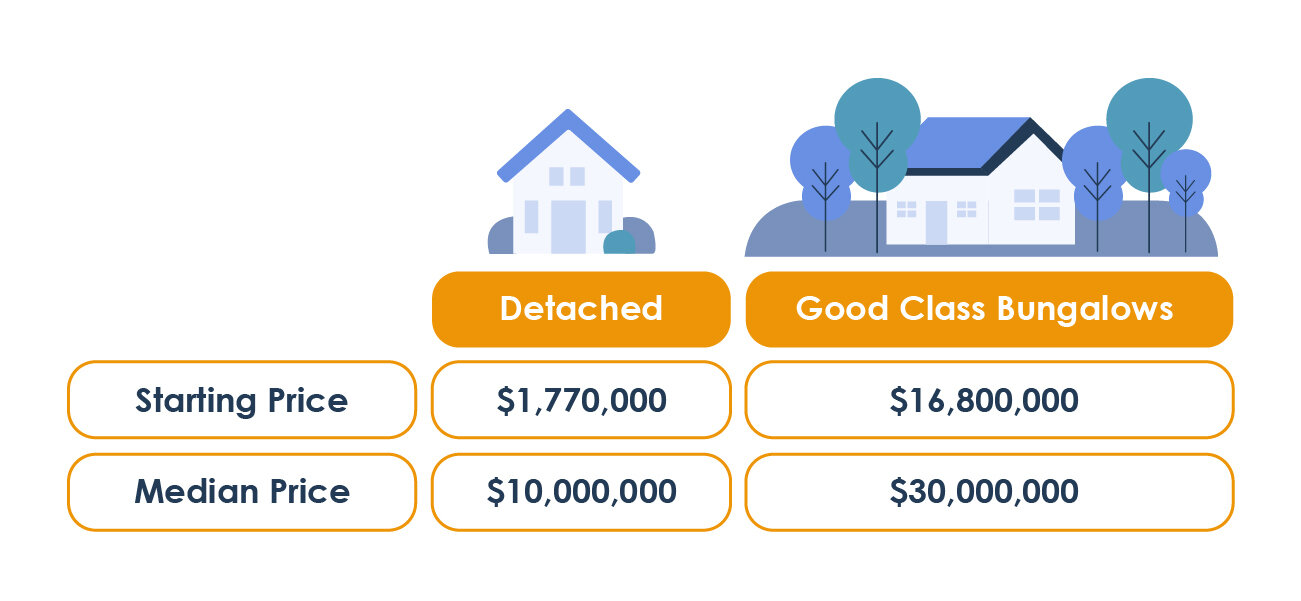

Based on the past transaction prices between May 2020 to June 2021 derived from URA, the price of a GCB starts from a whopping $16.8 million, and is a significant jump from the starting prices of the other detached bungalows, starting from $1.77 million. Also from the median prices of GCBs as compared to the other detached bungalows, we can also tell how GCBs are the creme de la creme for landed properties in the real estate market.

And even though landed properties, or housing in general, have changed over the years to adapt to the limited land space in Singapore, these magnificent bungalows remain. Having been restored or restructured over the years, they bear hints of the architecture that has been preserved and passed down over generations. This, of course, along with the fact that there are a limited number of such bungalows to begin with, contributes to the exclusivity of owning a GCB.

One such example is a GCB located in 5 Lermit Road, which is the family home of C A V (Victor) Chew. Victor Chew was an important architect who contributed a lot to the post-colonial bungalows upon his return to Singapore after the graduation from Cambridge University and Regent Street Polytechnic School of Architecture in London. His personal style of architecture is clearly reflected in the design of the house, even his own residential GCB. And until today, it still stands strong.

GCBs can’t be helped but be part of the dreams of many. And while owning a GCB seems like a dream too good to come true, it doesn’t hurt to appreciate the architectural splendor and the history behind it right?

In the meantime, stay tune for our next article in the Landed Luxuries series to find out more about some of the previous and current owners of GCBs.

We would like to credit the information, photographs and maps in this article to the beautifully written “Singapore Good Class Bungalow 1819 – 2015” by Professor Robert Powell.

Join our Telegram Channel

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel